‘Christ Is King’ Is the Woke Right’s ‘Black Lives Matter’

What was once a phrase of religious affirmation has now become a tool for extremist groups seeking to advance exclusionary and, increasingly, openly antisemitic narratives.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

Dr. Colin Wright is the CEO/Editor-in-Chief of Reality’s Last Stand, an evolutionary biology PhD, and Manhattan Institute Fellow. His writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Times, the New York Post, Newsweek, City Journal, Quillette, Queer Majority, and other major news outlets and peer-reviewed journals.

For centuries, the phrase “Christ is King” has held a sacred place in Christian theology, emphasizing Christ’s divine authority as a moral and spiritual guide. Its theological roots are deeply embedded in scripture and tradition, particularly in Catholic liturgy, where Pope Pius XI officially instituted the Feast of Christ the King in 1925 as a response to the rise of secular ideologies like nationalism and communism. Historically, the phrase has been a declaration of faith, reinforcing religious devotion rather than serving as a political statement.

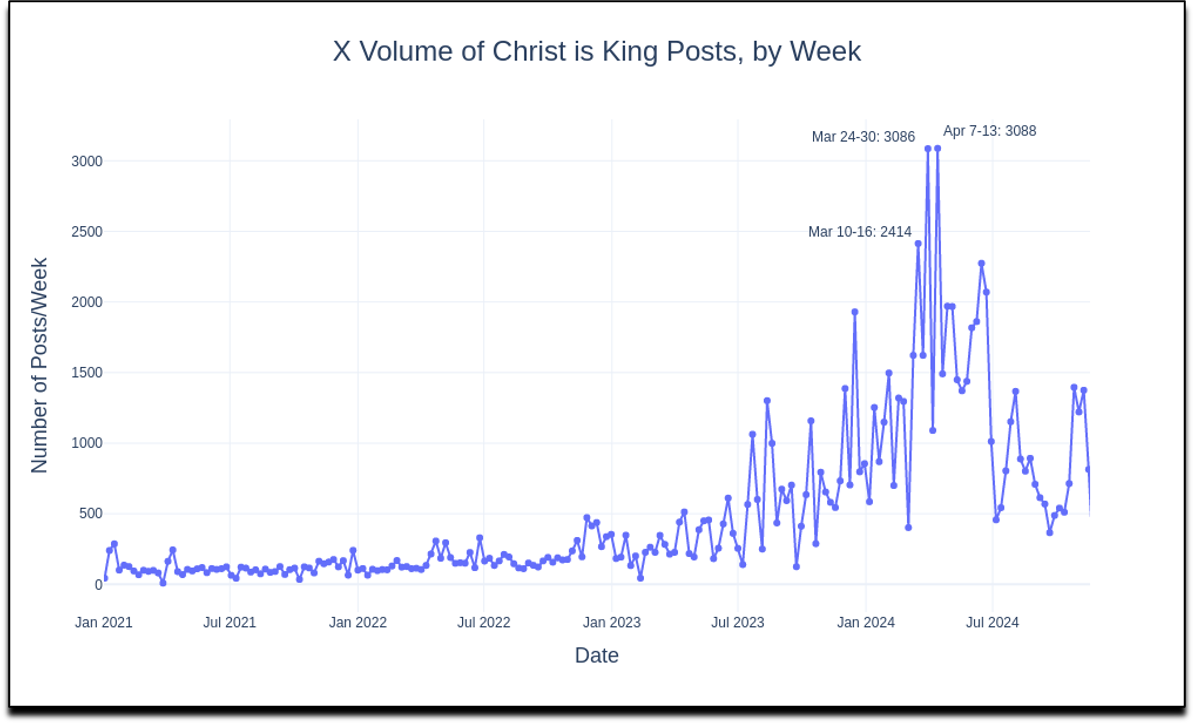

However, its meaning has shifted dramatically in the digital age. Before 2021, “Christ is King” was sparsely used online outside of religious contexts. But in 2021, it began appearing more frequently in conservative circles, often as a cultural counterpoint to left-wing secularism. This shift was exacerbated by figures such as Nick Fuentes, who, during the Million MAGA March in 2020, used the phrase as a chant among his supporters, blending Christian rhetoric with nationalist ideology. Since then, its use has skyrocketed, with mentions of “Christ is King” on X (formerly Twitter) increasing more than fivefold between 2021 and 2024.

What was once a phrase of religious affirmation has now become a tool for extremist groups seeking to advance exclusionary and, increasingly, openly antisemitic narratives.

A recent study by the Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI), titled “Thy Name in Vain: How Online Extremists Hijacked ‘Christ is King,’” and authored by Lee Jussim, Joel Finkelstein, and, most notably, Jordan Peterson, among others, found that in 2024, extremist figures—including white nationalists and radical Muslim influencers—were responsible for 50 percent of all “Christ is King” engagements. The report reveals a troubling pattern: an increase in antisemitic rhetoric, a deliberate hijacking of Christian identity for ideological ends, and a mainstreaming of coded hate speech disguised as religious conviction.

Like other powerful slogans that have been co-opted by political movements, its meaning is no longer dictated by its original theological intent but by the loudest voices that now wield it. This transformation is not unique; it follows a broader pattern in modern discourse, where seemingly indisputable beliefs and moral statements become ideological weapons. It bears striking similarities to how the phrase “Black Lives Matter” was politically co-opted in the 2010s—and again in 2020—turning a simple moral assertion into a divisive political tool.

In the following sections, I will first examine the NCRI report’s findings on the radicalization of “Christ is King,” detailing how extremists have systematically repurposed the phrase. I will then provide a more in-depth analysis of its rhetorical similarities to “Black Lives Matter,” illustrating how both phrases have been strategically manipulated to serve broader ideological agendas.

A central figure in the transformation of “Christ is King” from a religious affirmation to an extremist rallying cry is Nick Fuentes. Fuentes, a white nationalist and self-proclaimed Christian nationalist, has played a pivotal role in embedding the phrase within the rhetoric of white supremacy and antisemitism. His use of “Christ is King” dates back to the Million MAGA March in 2020, where he led chants of the phrase among his supporters, signaling its transition from one of theological devotion to political provocation. Over the years, Fuentes and his followers have strategically repurposed the phrase, presenting it as a call for Christian dominance while intertwining it with antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Building on this shift, researchers at the NCRI sought to trace the broader trajectory of how “Christ is King” evolved from a traditional religious statement into a coded symbol for extremist groups. To do so, the NCRI conducted a comprehensive analysis of social media trends, engagement patterns, and linguistic shifts. Their methodology involved gathering and analyzing nearly 200,000 posts across X and Instagram, spanning from 2011 to 2024. This large dataset allowed researchers to track both the rise in usage and the semantic evolution of the phrase.

One of the key findings of the report was the dramatic increase in mentions of “Christ is King” on X, which rose more than fivefold between 2021 and 2024.

This surge was not organic but driven largely by extremist figures, who collectively accounted for 50 percent of the phrase’s engagement in 2024. In particular, the study found that individuals like Jack Posobiec, Candace Owens, and Jake Shields played the largest role in amplifying the phrase, repurposing it from its traditional religious meaning into a political and exclusionary message.

A striking aspect of the NCRI’s findings was the unexpected alliance between far-right Christian nationalists and extremist Muslim influencers. Figures such as Sneako and Andrew Tate, both of whom embrace and promote toxic interpretations of masculinity and religious identity, frequently used “Christ is King” as a rallying cry. Their messaging often positioned Jews as a common adversary to both Christian and Muslim interests, suggesting a deliberate effort to unite disparate extremist factions under a shared ideological umbrella.

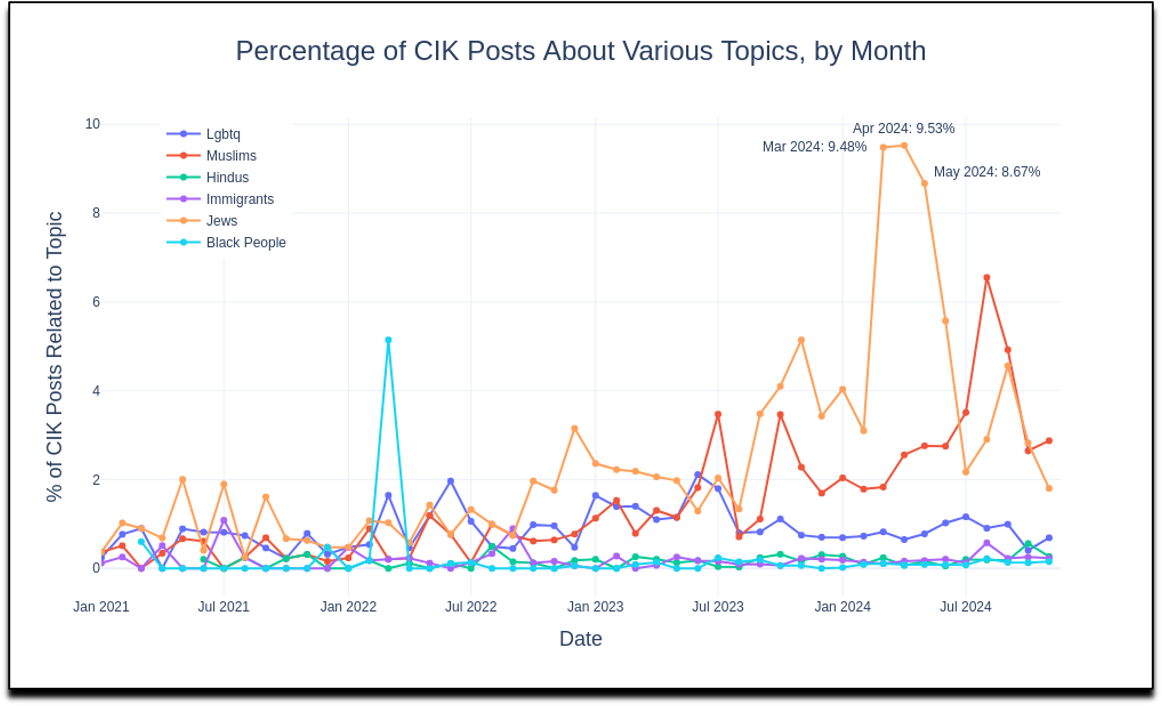

The analysis revealed this growing association between “Christ is King” and antisemitic rhetoric. Using advanced language modeling, researchers found that nearly 10 percent of all posts mentioning the phrase in March and April of 2024 either referenced Jews or contained explicit antisemitic content. In fact, the term “Jew” became the single strongest association with “Christ is King” in 2024. Other minority groups did not exhibit a similar rise in mentions during this time.

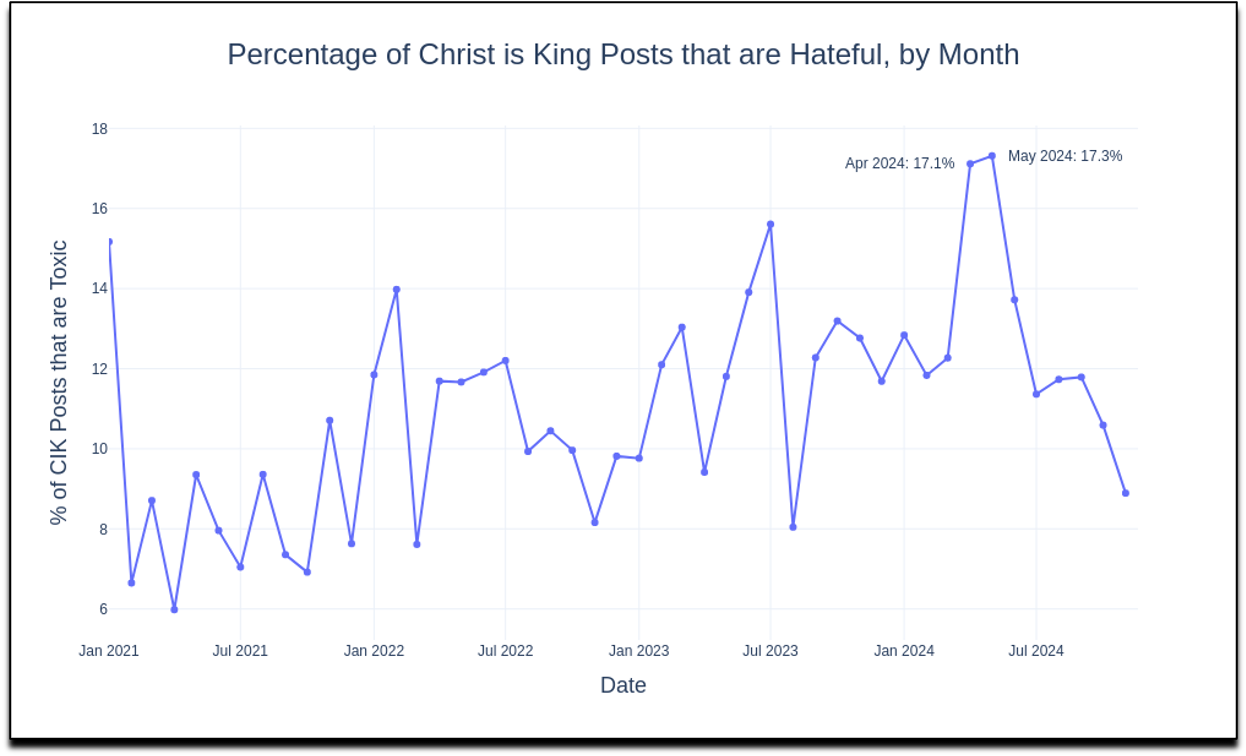

Beyond influencer activity, the NCRI’s machine-learning models detected a steady rise in hate speech associated with “Christ is King.” In 2021, approximately 9 percent of posts containing the phrase were flagged as hateful; by 2024, that number had risen to 17.3 percent. The peak occurred in May 2024, aligning with a surge in extremist-driven online discussions. This escalation demonstrates how “Christ is King” has been systematically repurposed by a radical movement as a dog whistle for antisemitic and exclusionary ideology.

A particularly notable moment in the report’s findings was the unprecedented spike in “Christ is King” discourse during Easter 2024. Traditionally, mentions of the phrase aligned with Christian holidays such as Easter and Christmas, driven by genuine religious observance. However, the 2024 surge was different. Rather than faith-based discussions, the majority of high-engagement posts were politically charged and often linked to antisemitic conspiracy theories. Candace Owens, in particular, played a primary role in this wave of online activity, using “Christ is King” in posts that promoted theories about Jewish control of media and global affairs. Her statements were quickly amplified by a network of extremist influencers, demonstrating a coordinated effort to inject these narratives into mainstream digital discourse.

The transformation of “Christ is King” follows a rhetorical playbook similar to that of “Black Lives Matter.” On the surface, both phrases express morally unobjectionable truths: of course, Christ is King to Christians, just as black lives (should) matter to everyone. However, in both cases, ideological movements have hijacked these statements to push extremist views.

The Black Lives Matter movement capitalized on the phrase to promote policies rooted in critical race theory (CRT) and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), particularly the “equity” aspect, which many rightly viewed as a form of systemic racial discrimination. Those who hesitated to endorse the phrase “Black Lives Matter” wholesale, often due to concerns about the radical political agenda attached to it, found themselves accused of racism. The distinction between the plain moral truth (black lives matter) and the movement (Black Lives Matter) was deliberately blurred, ensuring that anyone who rejected the latter could be framed as rejecting the former.

A similar bait-and-switch is now unfolding on the Right with “Christ Is King.” The phrase is not merely an expression of Christian belief; it is being used as a social litmus test. Just as questioning BLM’s agenda led to accusations of racism, expressing concerns over the radicalization of “Christ is King” now leads to accusations of being a weak or inauthentic Christian. “Oh, so you DON’T think Christ is King?” This social pressure coerces Christians into amplifying a phrase that has been strategically linked to a radical ideology, much like progressives were once pressured to embrace the ideological baggage of BLM.

By conflating agreement with the phrase itself with the broader political motives of those pushing it, this strategy manufactures the appearance of widespread support. Just as BLM used moral blackmail to push divisive policies like CRT and equity-driven racial preferences, the “Christ Is King” movement is leveraging religious solidarity to launder anti-Semitic ideas into mainstream discourse. The irony is that many conservatives, particularly those who opposed BLM for precisely this kind of rhetorical sleight of hand, are now embracing the “Christ is King” campaign without recognizing its underlying function.

If conservatives do not wake up to this dynamic, they will find themselves in the same position progressives did with BLM—forced to defend positions they never actually held, all because they were unwilling to challenge the misuse of a seemingly uncontroversial phrase.

The phrase “Christ Is King” is not the problem. The problem is the agenda that is hitching a ride on it.

Understanding how ideological movements manipulate language is crucial to resisting their influence. If we are to preserve the integrity of language as it relates to religious and moral beliefs, we must refuse to let bad actors dictate the meaning of our most cherished expressions.

You made it to the end! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below to show your support. Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication, and your help is greatly appreciated.

I know someone who when saying goodbye would say "Have a blessed day!". She was from the south, and a church goer. I knew her well, and understood that she was simply being kind. On the other hand, when hearing "Have a blessed day," a co-worker of ours would get agitated, thinking it was some kind of subversive phrase to get people into a proper church (I guess). The offended person was CATHOLIC, and went to church most Sundays. She was also pro-abortion (or, "Pro Choice if you like) and the particular parish she went to was extremely progressive....and the church Joe Biden attended when he did go to church.

Chill people! Sometimes words actually do mean what they say. Carry on Christians!

I dunno. I kind of see where you are going with it being a bit like the phrase “Black Lives Matter”, but you’ve not really convinced me that it’s anti-Semitic. Maybe if I read the article you reference I’ll change my mind, but for now I’d like to point out that sections of the Right who cry anti-semitism every five seconds sound like the woke left when they call everything racism.