‘Positionality Statements’ Undermine Scientific Integrity

By shifting attention away from methods and toward identity, positionality statements may actually increase bias.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

Dr. Colin Wright is the CEO/Editor-in-Chief of Reality’s Last Stand, an evolutionary biology PhD, and Manhattan Institute Fellow. His writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Times, the New York Post, Newsweek, City Journal, Quillette, Queer Majority, and other major news outlets and peer-reviewed journals.

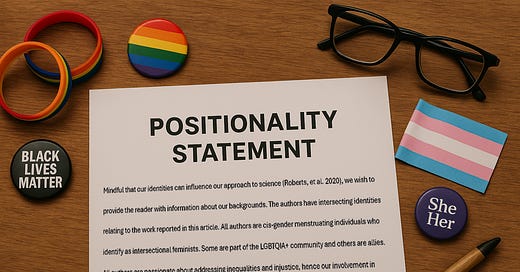

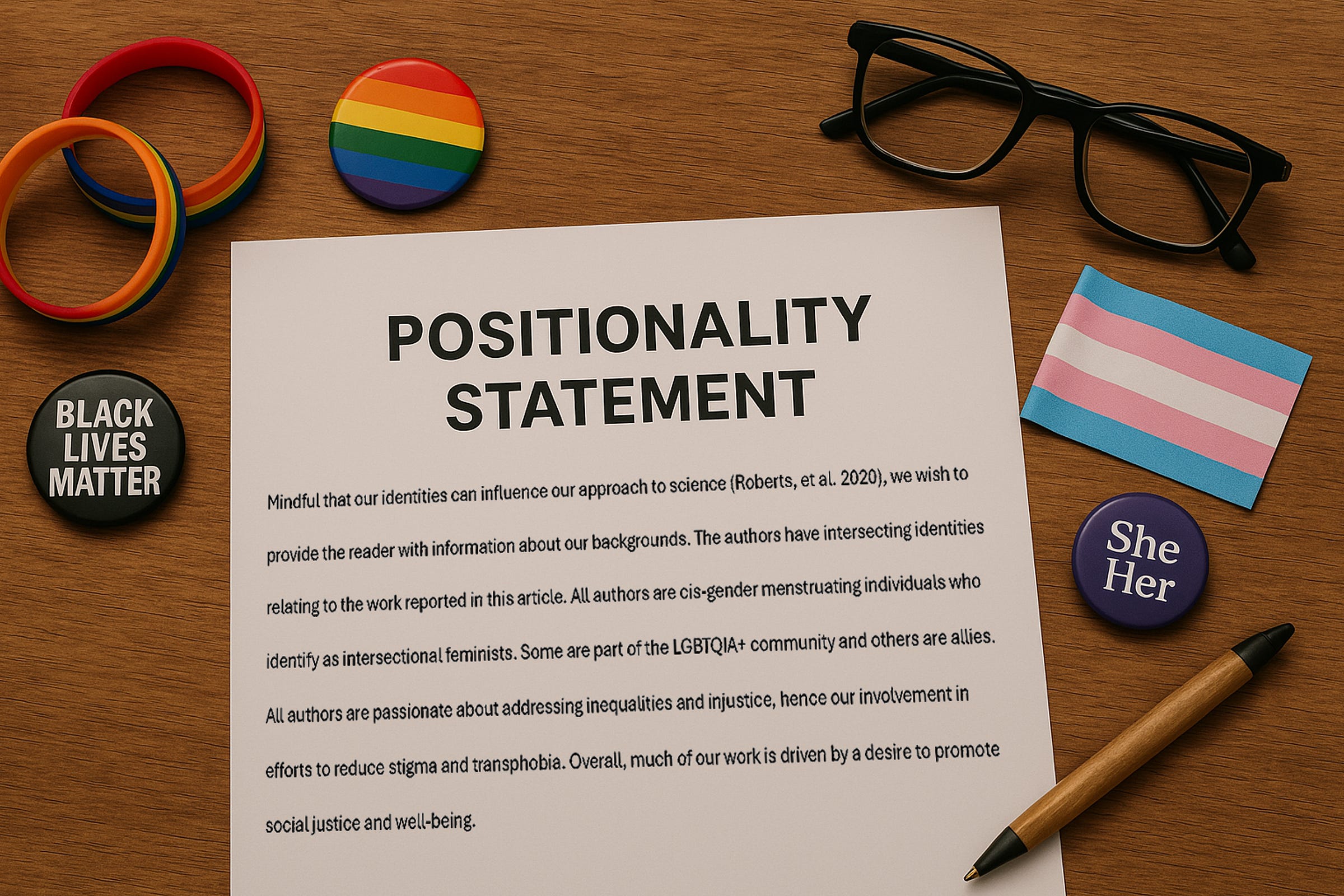

Some readers may know that I often post ridiculous, ideology-driven academic papers and dissertations on X (formerly Twitter). It’s become a bit of a hobby—calling out how certain fields have drifted into performative activism disguised as serious scholarship. Some of the worst examples turn into full-blown posts here on Reality’s Last Stand, where I break down not just what’s wrong with them, but why everyone should care. However, there’s one academic trend that I repeatedly encounter but rarely highlight, perhaps because it’s become so common it fades into the background: the “reflexivity” or “positionality” statement.

I recently posted an especially absurd example on X, where the authors felt the need to let readers and potential reviewers know that they were all “cis-gender menstruating individuals who identify as intersectional feminists,” among other things.

Although these statements are most commonly found in the usual “woke” or “grievance studies” disciplines—fields that openly reject traditional scientific norms and standards—they are now creeping into mainstream, even top-tier, science journals. What started as a practice mostly limited to qualitative research in the social sciences has now spread much more widely. Take this example from a paper published in Nature Ecology & Evolution:

We should all certainly hope that the authors have been “educated in a predominantly Euro–American cultural context and scientific tradition,” given that the paper is published in a Europe-based science journal!

So what’s going on here? What exactly is a positionality statement, and why are researchers including them?

In short, a positionality (or reflexivity) statement is a formal acknowledgment by researchers of their own social identities—such as race, gender, class, sexuality, or other “lived experiences”—that may have shaped their perspective on the research topic. Think of it like a conflict-of-interest (COI) disclosure, except instead of revealing financial ties that might compromise a researcher’s objectivity, the author is confessing their social location and ideological commitments.

Supporters of this practice claim it promotes transparency. They say it’s just being honest: all people have biases, so why not acknowledge them up front? But the reasoning gets much more ideological than that. Their view isn’t just that people are shaped by their environment—which is obviously true—but that all knowledge is socially situated. This belief comes from a branch of feminist and postmodern philosophy known as “standpoint epistemology.” According to this view, people from marginalized groups enjoy a kind of “epistemic privilege”: because of their lived experiences, they are thought to have special access to certain truths, especially about oppression and injustice. However, this epistemic privilege has been extended to scientific truths as well. The fatal flaws in this philosophy will be made clear later on.

On the surface, positionality statements seem noble—who could be against reflection and transparency? But when you start looking at it more closely, many serious issues begin to surface.

The most thorough critique of positionality statements I’ve seen comes from a paper titled “Positionality and Its Problems: Questioning the Value of Reflexivity Statements in Research” by Jukka Savolainen, Patrick J. Casey, Justin P. McBrayer, and Patricia Nayna Schwerdtle, published in Perspectives on Psychological Science. In it, the authors lay out three major objections to the practice, each of which should give serious pause to anyone who believes science should be guided by evidence and logic instead of ideology.

Positionality Statements Are Fundamentally Flawed

The first objection is philosophical: positionality statements are inherently self-defeating. They attempt to disclose how a researcher’s identity may shape their perspective on a topic, but the very epistemology that justifies positionality statements—standpoint theory—also undermines the credibility of any such self-disclosure.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Reality’s Last Stand to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.