The Quackery of Columbia’s Racialized Medical Research

A Columbia professor’s NIH-funded study linking historical lynchings to negative cognitive health outcomes for black people fails to meet basic scientific standards of rigor and validity.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

This article was originally published by Do No Harm.

A recent article by Chris Rufo and Hannah Grossman of the Manhattan Institute offers an unflattering profile of Dr. Jennifer Manly, a neuropsychologist and Columbia professor. Manly is an agitator within the pro-Hamas campus movement. Her activism spills into her research, much of it based on “the so-called social determinants of health thesis, which posits that racism, sexism, and homophobia can cause brain disease in ‘Black and Latinx communities.’”

Rufo and Grossman note that critics have described the thesis as “pseudo-science.” Manly and her defenders would surely disagree, pointing to her impressive collection of scholarly publications and citations. However, peer review in medical journals is often just as much a screen for ideology as it is one for rigor. A careful examination of a study that Manly recently co-authored makes for a useful illustration of just how faulty this line of research is, and why it is incumbent upon the NIH to stop funding it.

The study, “’Rest of the folks are tired and weary’: The impact of historical lynchings on biological and cognitive health for older adults racialized as Black,” was published in the journal Social Science & Medicine by ten authors, with Manly’s name appearing last.

As the title suggests, the study examines the effect of lynchings on health outcomes. It claims to find that residing in states that historically had more lynchings of black victims causes black subjects to experience a greater increase in a measure of inflammation and a greater decline in cognitive function. The theory it offers to account for these findings is that experiencing lynchings activates a “stress response in early childhood” that contributes to adverse health outcomes later in life.

The article only supports this claim by using a convoluted and indefensible research design and by interpreting the results in implausible ways. Rather than devising a measure of lynching that might capture the likelihood that one was exposed to lynchings, they discard information and dichotomize the 37 states that had any lynchings of black people into having above median or below median number of lynchings. As they describe it, “we dichotomized the variable at the 50th percentile (median), where less than the median corresponded to states with 1 lynching and greater than the median corresponded to states that had 2 or more lynchings.”

As one of many examples of sloppiness, the median number of black victims of lynchings among the 37 states with at least one lynching is 16, not 1 or 2. And the median among all 44 states in the Tuskegee Institute’s data set is 5. Another egregious example of sloppiness is that the article mis-describes the Emancipation Proclamation as having been issued in 1864, when it was actually issued on January 1, 1863. And in another error, the text describes the main result inconsistently with how it is described in the tables.*

Regardless of how the researchers divided states into above and below median lynching categories, dichotomizing the data threw away information that prevented a more fine-grained examination of the health effects of lynchings. The effect of living in Mississippi, which had 539 black victims of lynchings between 1882 and1968, is treated the same as living in Virginia, with 83 lynchings, or Illinois, with 19. All would be above median, however they calculated it.

The researchers make no adjustment for the population of states, so that California, with 2 black victims of lynching, is treated the same as Montana, which also has 2. If the researchers are hoping to measure exposure to lynching, failing to differentiate between the size of states is a serious shortcoming.

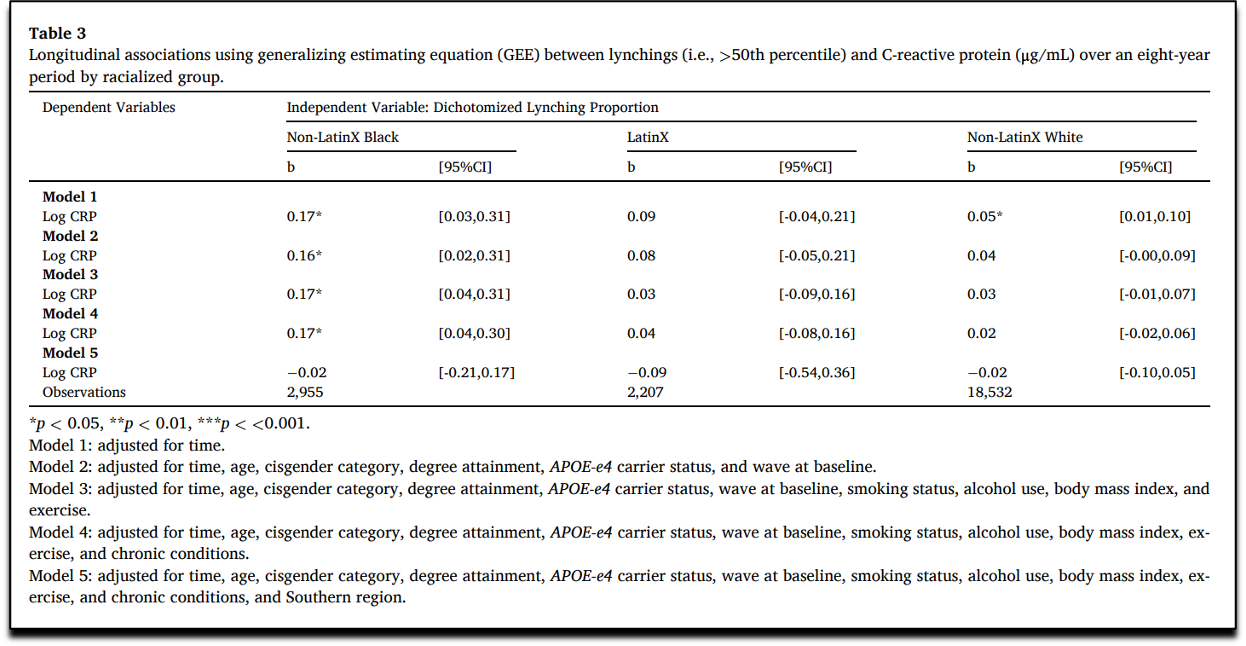

But the most serious failure of the study is that the results of its fully specified model do not find that health outcomes are worse among black subjects in states classified as having a higher number of historic lynchings. As can be seen in Model 5 of Table 3, being in a state with above median historic lynchings is not significantly related to the CRP measure of inflammation among black subjects.

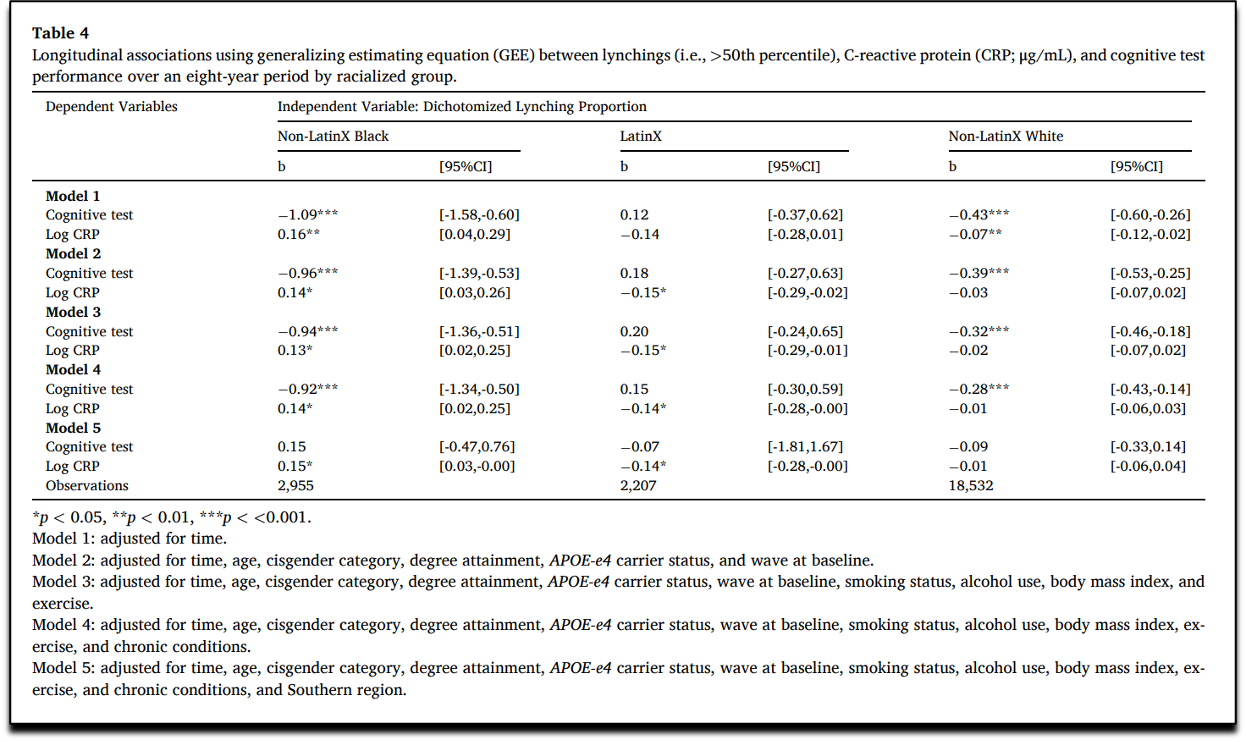

And in Model 5 of Table 4, residing in a state with an above median number of historic lynchings is not significantly related to the measure of cognitive performance among black subjects.

In model 5, the researchers add to their set of controls a variable for whether the state is in the Census definition of the South. So, what their research really shows is that black subjects who live in the South have worsening measures of inflammation and cognitive performance, not that historic lynchings contribute to adverse health outcomes. That is, within the South, being in a state that had above or below median numbers of lynchings is unrelated to health outcomes. And within the North, residing in a high or low lynching state also made no difference. The main factor driving their result is that health outcomes are worse in the South, even when controlling for a handful of other risk factors.

In the discussion section, the researchers attempt to dismiss these null results by noting that “the high overlap of participants living in U.S. South and a state with high lynching proportions may have induced some collinearity in our fully adjusted models.” Of course, there would be less collinearity if the researchers had not dichotomized the measure of lynchings. Regardless of their explanation, the fact remains that they have null results when controlling for region. This means that health outcomes for black subjects appear to vary based on the region in which they live, not the number of historic lynchings.

The claimed finding that exposure to lynchings of black victims by black subjects causes adverse health outcomes is further undermined by results that are inconsistent with their causal narrative. Specifically, they find that white subjects also have significantly lower cognitive performance in states with above median number of lynchings of black victims in all models except the one that controls for the South that also produces null results for black subjects.

The researchers attempt to explain this unexpected finding by arguing: “it is likely that structural racism against people racialized as Black co-occurred with structural racism-related factors, such as economic underdevelopment, which created a ‘universal harm’ (Brown and Homan, 2024) that also adversely impacted people racialized as White in the U.S. South.” By acknowledging that other factors, such as economic underdevelopment in the South may account for the adverse health outcomes of white subjects, it is unclear why this could also not be the explanation for the negative outcomes for black subjects.

Lastly, the claim that these subjects would have been exposed to lynchings strains credibility given how almost 99 percent of lynchings occurred before the average subject in the study could have been aware of them as a child. The average age for black subjects in the study was 67.68 when baseline data was collected in 2006 or 2008, meaning they were born around 1939. After 1942, when these subjects would have been three years-old, there were only 26 lynchings with black victims recorded nationwide in the Tuskegee Institute data set used by the researchers. That means that over 99 percent of the lynchings with black victims used for the study’s analysis occurred before the average subject could have been aware enough to have “experienced” it.

The only way that black subjects could have been affected is by living in the kind of state that had previously witnessed lynchings of black victims. But just as economic development is a different causal mechanism than the stress of having experienced lynchings, the conditions that facilitated lynchings in certain states before subjects could have been aware of those events are not the same thing as lynchings themselves.

All that this study demonstrates is that black and white subjects in the South have worse health outcomes than subjects in other regions. We have no way of knowing whether lynchings, economic conditions, or other factors in the past or present contributed to these negative health results. Claiming that the stress of experiencing lynchings caused these health problems is without any scientific basis. No credible scientists would use this evidence to make that claim and no credible scientific journal would publish and stand by these results. No credible health agency should be funding this pseudoscience, either.

Jay Greene, PhD is a senior fellow at Do No Harm.

* In another example of sloppiness, the article twice describes the effects as 18.5%: “Black that lived in states with higher proportions of lynchings (in midlife) experienced 18.5% (95% CI 3%, 36%) higher circulating CRP levels than participants racialized as Black that lived in states with lower proportions of lynchings.” But the coefficient in Table 3 is .17 and .185 does not appear anywhere in the tables of results.

Wow, you made it to the end! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below to show your support. Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication, and your help is greatly appreciated.

Negative cognitive health outcomes are more likely caused by poverty and junk food. You could probably show a correlation between brain degradation and availability and use of Chick-fil-A, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Raising Cain and other fast food chains and low cost grocery stores. Surprisingly enough, those junk food outlets tend to be frequented by poor people, both black and white.

I can't express how much of a relief I feel that some of this pseudoscience will soon be ended, along with the idiocy of gender ideology. I only wish we could trust Republicans to do right by us instead of just destroying the other side.

So it would appear that NIH has money to burn. This is exactly how one goes about getting their funding cut. Done in by their own stupidity..........though there may be grant money available to study that conclusion.